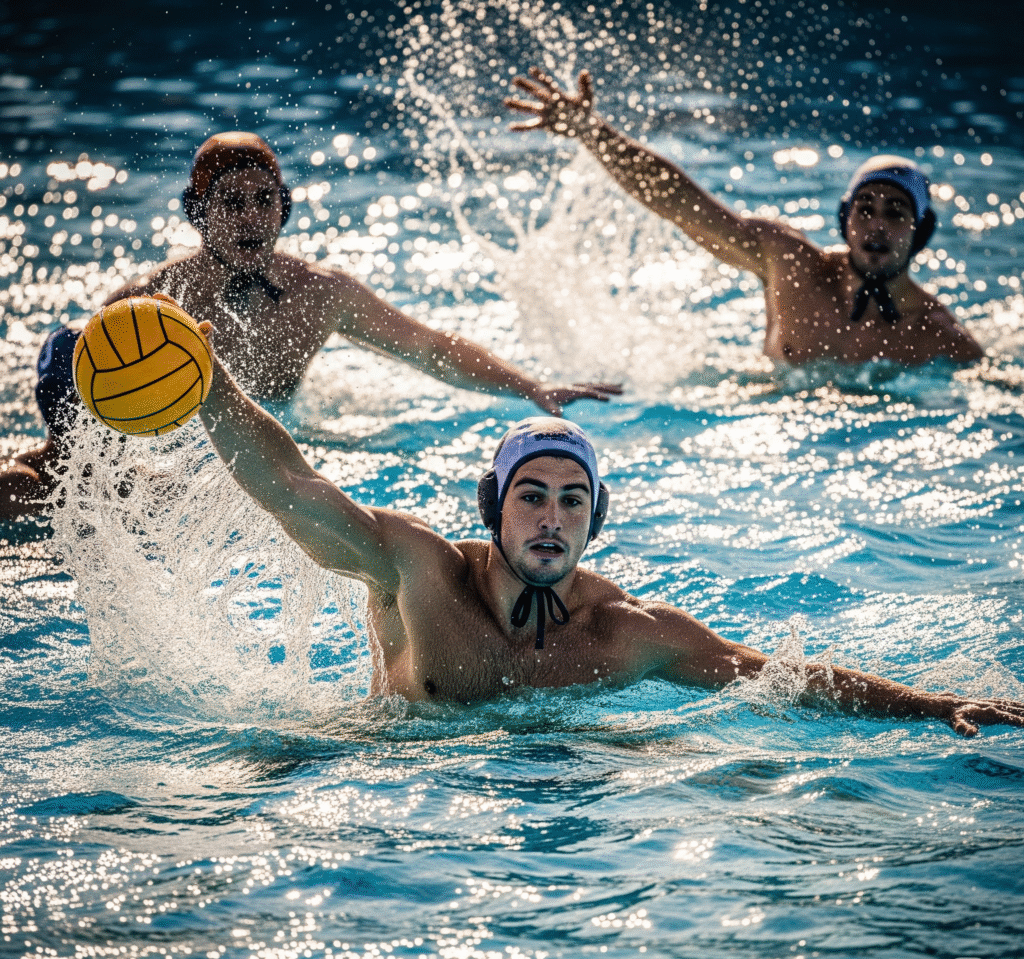

The last time officials from Swimming South Africa were spotted, it was with bloody noses and sore heads.

This was because of the humiliating loss the ruling body of SA aquatic sport took in the Western Cape High Court, where a judge ruled that the breakaway South African Water Polo (SAWP) organisation has the legal right to exist.

SSA’s bid to interdict the upstarts was a massive embarrassment in keeping with the general state of dysfunction that abounds.

The court found SSA does not have an exclusive, perpetual right to govern water polo in South Africa. It also upheld SA Water Polo’s constitutional right to freedom of association. SAWP was formed by disillusioned coaches, players, and officials aiming to improve the sport’s governance and performance. They had simply had enough.

While SSA remains the officially recognised federation, the ruling opens the door for SAWP to potentially become the national governing body in the future.

This is the same SSA which last month failed to acknowledge the death of Joan Harrison, South Africa’s first Olympic swimming champion.

This is the same SSA which failed to mention Tatjana Schoenmaker on its social platforms when she was winning gold at the Olympic Games.

This is the same SSA which revels in controversy.

In recent years there have been governance and leadership challenges with the federation’s executive, including president Alan Fritz, serving beyond the constitutional three-term limit, raising legal and ethical questions.

Additionally, elite artistic swimmers Jessica Hayes-Hill and Laura Strugnell successfully challenged SSA’s disciplinary actions after being controversially sent home from the 2024 World Championships, leading to a R7,2-million lawsuit.

“Deceitful actioning of training protocol without management approval,” was cited by SSA, a vague charge that has raised eyebrows.

SSA also admitted to an unconstitutional clause in its constitution forbidding members from suing the federation, promising amendments. Allegations of poor leadership, inadequate communication, and insufficient support for non-swimming aquatic sports persist, fuelling calls for urgent reform and greater transparency.

The court ruling sets an important precedent: dissatisfaction with poor governance can lead to the rise of alternative structures, challenging entrenched federations. Given South Africa’s widespread sports administration crises, including financial mismanagement and weak accountability, this could inspire similar breakaways, underscoring the urgent need for reform to restore trust and stability.

The ruling is a wake-up call. Will the powers that be answer it?

And will other sports pay heed?