Everywhere Lennox Lewis has gone in Johannesburg this week, the shouts have rung out.

“You’re the best! You’re the greatest!”

Lewis just smiles. “You say I’m the greatest. My hero was Muhammad Ali – I can’t be greater than him,” he told a gathered crowd at Emperors Palace, not a long way from where he fought in South Africa 23 years ago.

On that occasion, Hasim Rahman produced a massive upset, knocking him out in the fifth round for the undisputed heavyweight championship.

Lewis is comfortable to talk about that moment, not least because he avenged the defeat in spectacular fashion seven months later.

He met Nelson Mandela in the week of the first fight and the former president had VIP billing alongside Will Smith and others at Carnival City.

“Although I lost that fight, Mandela came to the fight and said to me ‘You need to keep your right hand up higher’. He said ‘don’t worry, you’ll get him next time’. When he said don’t worry, it let the stress off me. I felt that this is a man who believes in me, so next time I’ll call out his name and beat Hasim.”

And he did, and thus began an unusual friendship that included calls from Mandela to Lewis ahead of his big fights. “I didn’t realise how much this man loved boxing. All he wanted to know about was boxing. He was excited.”

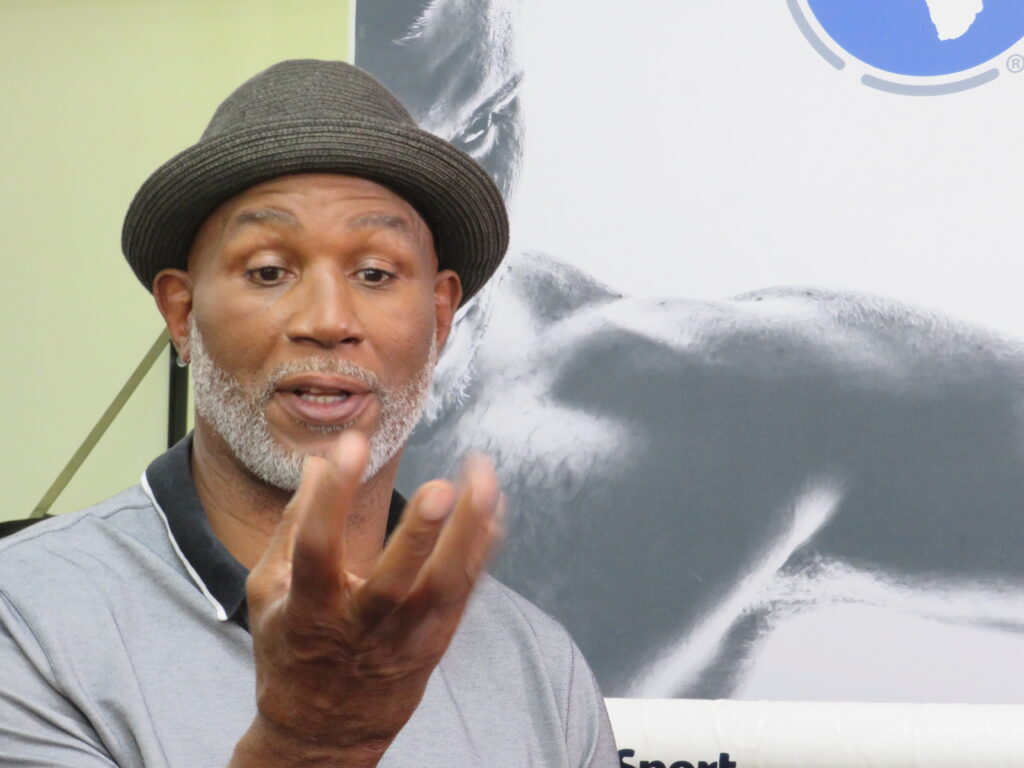

Now 59, lean and lightly bearded, Lennox still carries himself with an air of cool, helped these days by a bowler hat he wears with the insouciance of a man comfortable in his own skin.

He’s a busy traveller, taking assignments in Germany, the UK and Saudi Arabia in recent weeks. He was in Texas for the Mike Tyson-Jake Paul fight and he does commentary stints across the globe. Smart and articulate, he’s become something of an elder statesman of the sport, a sensible sounding board and arbiter of what’s good and what’s not in boxing.

He doesn’t mind celebrity boxing, reckoning that anything that puts new eyes on the sport can’t be a bad thing. He jokes, too, that he’d come back and fight anyone, even now – “if the money is right”.

He’s watched the advancing power of Saudi Arabia with keen interest and likes what moneyed promoter Turki Alalshikh is doing. “He’s putting a lot of money in and boxing needs that sort of help.”

The former champion has fond memories of his youth, having played every sport he could before wising up to the virtue of an individual sport like boxing.

“I didn’t have to worry about my teammates dropping the ball,” he says. Any mistakes would be his own.

He competed in his first Olympics at the age of 18, in 1984. He recalls how he had limited sparring and international experience.

“I wanted to win the gold so bad.”

Trouble was, he was up against Tyrell Biggs, who was slick and more experienced. Lewis went after him hard in the first round, but Biggs was too clever and coasted to a decision in the quarterfinals.

Lewis simmered for years after. “I’m gonna get him back, I’m gonna learn everything I need to learn to do.”

Seven years later, smarter and stronger, he destroyed Biggs in the third round in his 18th professional bout.

(He also finally won Olympic gold, beating Riddick Bowe in the 1988 super heavyweight final).

He went on to capture the world heavyweight title in just his fourth year as a professional, beating Tony Tucker in Las Vegas in 1993, but stumbled against Oliver McCall the very next year.

“Everybody loves a winner. I was winning back then. When you lose, people say ‘What you gonna do now? For me, the journey wasn’t finished. It’s like falling off a horse. What do you do? You get back on the horse. I gotta jump back on. It was the only mistake I made. I put up my hand and he hit me round the side and everything went slow motion till I hit the ground. One vital mistake and one vital mistake can make history.

“I said, listen, my titles are on hold. I’m just lending them out. I trained harder, I came back and I won [the rematch]. Some of my people who were around me had walked away and thought that was it.”

The road back included a bruising fight against Ray Mercer in a tiny ring. Mercer had shown what he could do by destroying a game Tommy Morrison. Lewis was wary.

The hulking American rushed him and tried to smother him with punches and then hold on. Trainer Manny Steward urged Lewis to change tack, and he did, throwing back harder and faster. Hard as it was, Lewis prevailed.

Mercer is in the mix, but Lewis struggles to come up with a name for his toughest opponent. “Because I made my training so tough, my fights were easy.”

In 1999, he had his infamous showdown with Evander Holyfield for the IBF and WBC championships in Las Vegas. Despite his superior performance, Lewis was screwed by the judges, South Africa’s Stan Christodoulou being the only one to award the fight in his favour.

It went down as a draw on Lewis’ record, the only one of his career, but the public adulation was welcome compensation.

Speaking on Friday, Lewis believes he won over US fight fans because they love a good battle.

“I said that Evander Holyfield has never seen a boxer like me. When we got into the fight, the public never believed. Not even the judges believed. I won, but they said it was a draw. The reasoning is a judge got paid off to give it to Evander Holyfield.

“I was happy because the public is the judge and they got to judge. Everyone knew I was number one at the time.”

Lewis changed little for the rematch eight months later.

“I did it again. If it ain’t broke, don’t fix it, so I boxed the same way. He came in a little more anxious to win the second fight.”

This time, Lewis swept all three cards to be confirmed as the ruler of the division.

Having for years been compared to Mike Tyson, often unfavourably, Lewis was thrilled he got to settle matters in 2002.

“People said Mike’s the best, Evander’s the best, Lewis is the best. I wanted everyone to know who’s best.”

A heavy right cross in the eighth round settled the argument emphatically.

Lewis was always the patient boxer-puncher. Unlike Tyson, he was more measured, more technical.

“One thing I learned growing up: hit without being hit. You’ll have a more long-lasting life if you don’t get hit. That’s my message to young kids.”

Lewis is in South Africa scouting for opportunities in boxing and will also be at Emperors Palace to watch Kestna Davis, his Jamaican prodigy, square off against a local comntender.

He’s happy enough with the state of boxing, but questions the motivation of the current crop of elite heavyweights.

“They are looking for how much money they can get instead of glory. I went for glory. People won’t remember how much money I made, but they will remember what I achieved. That was important for me.”

He says HBO, the US television network, was keen to see him come back for one last major fight after he beat Vitali Klitschko. Lewis himself looked at the landscape, unimpressed by what he saw.

He felt he could dominate a new era, but opted instead to walk away – at the very top.

A champion to the end.

Lewis is in South Africa as a guest of Golden Gloves.