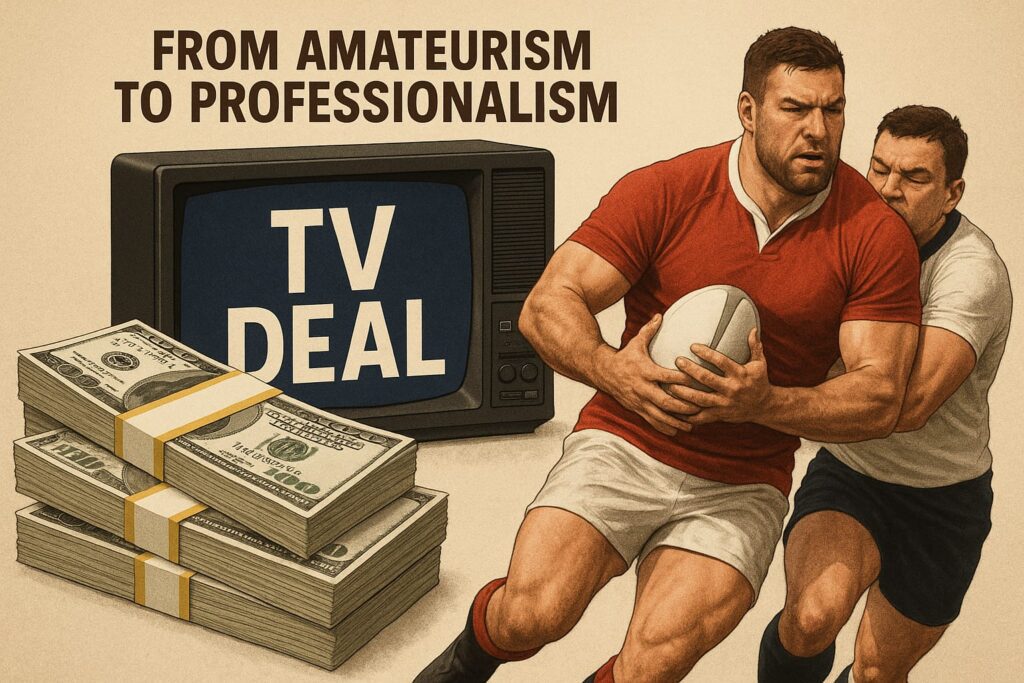

The 1995 Rugby World Cup didn’t just crown a champion team, it triggered the seismic shift to professionalism. Thirty years on, we examine how Rupert Murdoch’s millions changed rugby forever.

The story goes that when media titan Rupert Murdoch was watching Jonah Lomu tear up South African fields at the 1995 Rugby World Cup, he turned to a lieutenant and said, “Get me that man.”

Days later, he got his wish.

Today, 30 years ago, signatures were put to a contract that would effectively end over 100 years of amateur rugby.

Just four days out from the final, SA rugby supremo Louis Luyt had travelled to London to meet with Sam Chisholm of Murdoch’s News Corporation.

The late Dr Luyt recalled the meeting in Walking Proud, his autobiography.

He introduced his son, Louis jnr, who had tagged along. “Louis’s coming along, ‘to get some experience of how you men operate; to get a feel for how business is done at this high level’,” he said.

Chisholm chuckled. He was in a cheerful mood, obviously buoyed by the wild spectacle between England and New Zealand at Newlands, which he had watched the previous week from the comfort of his London home. If this was the kind of stuff he was purchasing, he seemed to have decided, it was definitely worth a pretty penny.

“Tell me what you have in mind,” said Luyt. “We don’t have much time.”

Chisholm agreed.

“We were thinking of $550 million.”

Luyt, representing the rugby powers of the southern hemisphere, said it was exactly $100 million below their asking price.

“No,” he said, “we need a little more than that, say $555 million. That would do it.”

Chisholm, according to Luyt’s telling, looked as if he might feign a heart attack.

Some back and forth ensued. The deal was done for a “nice-sounding triple five” over the following 10 years.

Chisholm’s attorney, Bruce McWilliam, tapped away at the keys of a laptop computer as the parties talked around the dining room table.

By lunchtime, an agreement had been cobbled together. For the total amount of $555 million, News Corporation (NewsCorp) acquired exclusive worldwide television, radio and video rights for all international and representative rugby union matches played in Australia, South Africa and New Zealand for the following 10 years starting in 1996. Each of the three participating nations undertook to do its best to sign up their own players and keep them to the contract.

Stars like Lomu, Francois Pienaar and Phil Kearns were duly kept in-house.

Lunch was taken, and Murdoch was consulted. The heads of agreement were ready. Luyt signed and initialled every page on behalf of Sanzar and Chisholm countersigned on behalf of News Corporation.

Rugby in the southern hemisphere had just become a half-billion-dollar business. No fanfare. No celebration. Merely a handshake and a hasty departure for Heathrow.

The World Cup final beckoned.

This deal served two main functions. First, it helped stave off an audacious threat by Australian media mogul Kerry Packer whose World Rugby Corporation secretly signed elite players, aiming to launch a rival professional league. This forced the International Rugby Board to act.

Reality had stared the IRB in the face. By the 1990s, several factors made continued amateurism unsustainable: “Shamateurism” and under-the-table payments had created a hypocritical, uneven playing field.

Also, professional rugby leagues in Australia, New Zealand, and the UK were increasingly luring top rugby union talent with lucrative contracts.

The increasing global popularity of rugby, particularly after the 1987 and 1991 Rugby World Cups, highlighted its commercial potential. Media companies saw the value in broadcasting rights, and the financial stakes began to rise.

On August 26, 1995, in Paris, the IRB unanimously declared rugby union an “open” game. This allowed official player payments, professional contracts, and the establishment of formal leagues worldwide.

The immediate impact was profound: players became full-time athletes, leading to higher fitness standards and more intense play. While challenging traditionalists, the sport rapidly commercialised with lucrative sponsorships and broadcast deals, fundamentally reshaping rugby into the global, professional spectacle it is today.

Thirty years on from those heady days, Got Game approached a cross-section of prominent rugby personalities to talk about the effects of rugby professionalism, the changes that have been wrought and whether the game is better or worse for having gone professional.

Rugby writer: Dan Retief

Rugby has switched from the game of the noble amateur to the unscrupulous mercenary and there is no doubt that it is has lost many of the values – mutual respect, sportsmanship, camaraderie, a sense of belonging – that existed before Rupert Murdoch said of Jonah Lomu “get me that man.”

Ironically, it is now a much smaller game since that day at Ellis Park that Louis Luyt told the gathered media that “there are 550-million reasons for doing this” to herald the advent of professional rugby.

The game is pretty much owned by the big pay television stations and the odd wealthy club owner and while there is much glitz and glamour at the top of the pyramid, the hinterland – far-flung rural areas, small clubs – where the game once flourished and occasionally produced a star, has been decimated.

Few now play for the love of the game and the big worry is that so many might be lost because they miss out on a professional break and, with fewer opportunities to play, simply walk away.

RWC 1995 TV director: Scott Seward

The arrival of professionalism in rugby union was a seismic shift for the sport, not only for players, administrators and coaches, but also for the broadcasters tasked with bringing the game into homes across South Africa.

While the transition came with its fair share of teething problems, especially for those managing the game’s new-found complexity, it marked a profound and welcome evolution for television coverage.

For broadcasters, professionalism represented a new era of structure, collaboration, and innovation, one that elevated the production and presentation of rugby to world-class standards.

One of the most immediate and valuable changes was the improvement in communication and coordination between rugby’s stakeholders: administrators, players, officials, sponsors, and broadcasters.

With professionalism came clearer roles, tighter timelines, and shared objectives, all of which helped ensure more consistent, sophisticated coverage. This synergy became the foundation on which broadcasters could build a more dynamic and engaging viewer experience.

The way rugby was presented on screen began to evolve. Live coverage gained structure and polish, with standardised running orders tailored for each competition. These formats were regularly reviewed and refined, ensuring that content remained fresh, relevant, and aligned with viewer expectations.

Beyond the live match itself, broadcasters began to expand their offerings. Pre- and post-match studio programmes became standard, previewing upcoming fixtures and providing analysis and context after the final whistle.

These wraparound shows served a dual purpose: deepening the viewer’s understanding and offering additional exposure for sponsors, a key consideration in a more commercially driven era.

Recognising the need to match resources to the importance of each game, broadcasters began grading competitions, from Test rugby down to schools-level matches. This allowed for smarter deployment of crews and equipment, with top-tier matches benefiting from more advanced setups and innovation in camera placement and production design.

Technology played a critical role in enhancing the viewing experience. From improved camera rigs to on-field microphones and drone coverage, the visual storytelling of rugby became more immersive.

At the same time, graphics advanced rapidly evolving from simple score tickers to rich, animated overlays, real-time stats, and eventually virtual reality sponsor graphics embedded into the field of play.

The professionalisation of rugby also extended behind the camera. The broadcaster invested in developing a skilled pipeline of talent introducing hands-on training at Craven Week for aspiring commentators, directors, camera operators, and crew, including women, who were increasingly included in roles previously unavailable to them. These opportunities not only strengthened the quality of broadcasts but also diversified and professionalised the industry from within.

New competitions, made possible by the professional era, also brought new opportunities. The Varsity Cup, a televised, sponsor-driven university tournament, became both a breeding ground for players and a training ground for broadcast teams. It showcased how rugby and television could grow together, creating value for players, fans, sponsors and production crews alike.

Crucially, professionalism also led to innovation in officiating. Referees were brought into the upskilling fold receiving recorded match footage and performance reviews to raise standards. The introduction of the Television Match Official (TMO) transformed decision-making, bringing clarity and accuracy, and giving viewers greater trust in the outcome.

Off the field, the focus on player safety gained prominence, with programmes like BokSmart (a joint initiative by SA Rugby and the Chris Burger/Petro Jackson Players’ Fund) coming to the fore. Television played its part by helping raise awareness and support for these vital causes, showing the game’s commitment to care alongside competition.

Looking back on nearly three decades of professional rugby, it’s clear that the game, and the way it’s covered, has undergone a remarkable transformation. For broadcasters, the professional era ushered in a golden age of collaboration, creativity, and accountability. Rugby became more than a sport on screen, it became a story, an experience, a production.

And for all involved, from players to producers, that journey has been both challenging and profoundly rewarding.

Rugby businessman: George Rautenbach

The game has been altered. It’s much faster and players are fitter than in amateur days. But there are too many rules and it is difficult to ref the modern game.

Everything in life has got to end and so did amateur rugby. It lost some of the traditions but so many have been kept. Look at how our Springbok team protects so many of the traditions.

The game is much better. Professional sport is expensive and rugby would not have survived [without professionalism]. Challenges remain but I think South Africa is managing them well.

Administrator (and then SARFU deputy president): Andre Markgraaff

The rugby world is still struggling to find its way around the financial pressures that all the clubs and provinces are under in the professional era.

The hope is that more competitions will create the necessary financial solution to the high demands of the professional game putting the game under more pressure. Playing B teams in the biggest club competition in the world must be a great concern for all stakeholders in the game.

Having played in the amateur era and coached in the amateur and professional eras I feel sorry for the professional players that missed the values and the real soul of the game.

The camaraderie, togetherness and respect are gone forever.

The professional game will go the rebel route because of unrealistic demands of player salaries.

RWC ’95 winner and broadcaster: Kobus Wiese

The game has lost quite a lot since it turned professional, although it should have turned professional many years ago – if that makes sense.

However, I think there’s more positive than negative. What has been lost is touring, like going to Australia or New Zealand for eight weeks, because that’s where you build character. That’s where you really discover young talent and take them out of their comfort zone and see what they can deliver.

But because of all the competitions and the big money, the long tours are no longer part of the game, which is a huge loss. Also part of the professional game is there are just too many rules in rugby. It’s as simple as that, and creates far more grey areas. There is confusion amongst supporters, players and referees, another big issue in rugby.

Player agent: Craig Livingstone

Over the past 30 years, professionalism has revolutionised rugby, transforming it from a game rooted in tradition to a global sport driven by performance, commerce, and media. Players are now faster, stronger, and better prepared than ever, with scientific training, tactical analysis, and year-round conditioning elevating standards to unprecedented levels. The global calendar, high-stakes competitions, and financial rewards have expanded the game’s reach and profile dramatically.

However, the amateur ethos, built on camaraderie, loyalty, and a deep sense of community, has been diluted. The game was once a brotherhood where club and country pride outweighed contracts; today, player movement, commercial pressures, and short-term performance often overshadow long-term development and identity.

Is the game better? In many ways, yes, technically and commercially. Players are faster, stronger, and more skilled thanks to advanced sports science, nutrition, and coaching. The overall standard of play is higher than ever.

The player earnings are at an all-time high and many of our top players play rugby outside of South Africa. Japan and France lead the way when it comes to paying players. The game has expanded globally, with emerging nations like Japan, Georgia, Portugal and Chile making strides. Rugby is no longer confined to traditional powerhouses.

Clear career pathways now exist for players from school level to the professional ranks, providing real opportunities and financial security that were impossible in the amateur era. South Africa boasts the best schoolboy rugby system in the world, a powerful, deeply embedded culture that produces extraordinary talent year after year.

From iconic inter-school rivalries to world-class coaching structures and passionate community support, our schoolboy system is a pipeline that consistently feeds the national game. The challenge and the opportunity lies in how we nurture and develop this foundation.

With better alignment between schools, unions, franchises, and national structures, we can not only retain more of our top talent but also broaden the base of participation and excellence. The future of South African rugby depends on how well we protect and evolve this unrivalled schoolboy ecosystem.

The women’s game has grown rapidly internationally, too, with increased investment, professionalism, and visibility, inspiring a new generation of players and fans.

Digital innovation, enhanced broadcasting, and fan engagement tools have transformed how supporters interact with the game, on and off the field.

There is a greater focus on concussion protocols, workload management, and mental health shows a growing commitment to player wellbeing.

An area where we have fallen short is having a structured and transparent transfer market, much like football to grow, professionalise, and sustain our beautiful game. A well-regulated transfer system would incentivise talent development, reward clubs and academies for nurturing players, and create new commercial opportunities across the rugby ecosystem.

By introducing mechanisms like transfer fees, and player trading windows, rugby can build a more sustainable economic model, reduce player poaching, and create a clear value chain from grassroots to the professional game. If we want rugby to thrive globally, we must embrace innovation and a formal transfer market is a crucial step forward.

And probably the most concerning state of our game is that, nearly 30 years after the sport turned professional, many national rugby unions and the majority of professional franchises continue to operate at a loss. This is not just unsustainable, it’s a warning signal. Despite rugby’s global popularity and deep cultural roots in countries like South Africa, New Zealand, France and the UK, the professional model has yet to consistently generate financial stability. If the game is to grow or even survive at the highest level, we need bold structural reforms, smarter commercial models, and a long-term commitment to building a more viable, global rugby economy.

Rugby has become more transactional and at times, soulless. The challenge now is to balance elite professionalism with the heart and humility that once defined rugby. After 30 years as an agent, I believe that preserving the spirit of the game while embracing its evolution is the key to its future.

International referee: Freek Burger

For more than two decades, I was immersed in the highest levels of officiating, serving as referee manager (1995) and citing commissioner at every Rugby World Cup until 2019. During this time, the selection process has ensured that only the top officials take charge of the game’s biggest moments. However, despite the pedigree of these referees, consistency in performances across tournaments has remained elusive.

The primary reason for this inconsistency lies in the grey areas within the laws – rules that remain open to interpretation, creating confusion and controversy. Key areas in need of urgent revision include:

Simplifying rugby’s laws – Too often, decisions are subjective, leading to discrepancies in rulings from one match to another. Clearer laws mean fewer debates and better officiating.

Revamping the TMO role – The Television Match Official (TMO) system, designed to aid referees, has often slowed the game down and introduced unnecessary interference. A more defined scope for the TMO could restore the flow of play while maintaining accuracy.

Carding issues – Yellow and red cards remain wildly inconsistent, often failing to reflect the true nature of an incident. The “balance of probabilities” approach used in foul play hearings, where the employer’s version is given more weight, is flawed and requires reassessment to ensure fairer disciplinary outcomes.

Beyond officiating, rugby’s structure and scheduling demand reconsideration. The overlap of competitions puts unbearable strain on players, who need designated rest periods to maintain peak performance and longevity in the sport.

Like players, referees should be dropped when their performances fall below expected standards. No one should be immune to scrutiny.

Also, tactical substitutions have shaped modern rugby, but a smaller bench could enhance the game’s integrity while retaining impact players.

There are law adjustments that could transform the game:

Scrum stability – Addressing endless reset scrums, which waste time and frustrate fans.

Obstruction rules – Tightening interpretations to allow cleaner attacking play.

Fair catch innovation – Inspired by the Varsity Cup, making high-ball contests less dangerous.

Increasing try value – Again, taking lessons from Varsity Cup, where rewarding attacking rugby has led to more excitement.

Breakdown clarity – Simplifying rules to ensure consistent enforcement and fair competition at the ruck.

Rugby is at a crossroads, and unless meaningful action is taken, the sport risks losing the clarity, fairness, and integrity that once defined it. Law reform must be prioritised, and officials must be held to the same accountability standards as players. Only then can we ensure that the game’s future remains as dynamic and exciting as its history.

Coach: Alan Zondagh (AZ Rugby Consultancy)

I was in the fortunate position to be involved full time in rugby since 1979.

My Currie Cup career started at the Eastern Province Union in 1989. During my time as coach of the WP team I was involved in the amateur game until 1995.

Nobody was prepared for the change [to professionalism]. The players were just happy that they were going to earn money but the officials at the union had no clue what the players’ contracts would entail. I then tried to grade my current squad into different categories so that the budget that I was given could be spread amongst the squad and staff.

Everything was new to us. As a coach I thought that we were now going to be able to train professionally but that did not happen. I was told that the players had to keep working in their jobs and that I could only train at night after work. So, on that side of professionalism, nothing changed. At the time I was heavily criticised by the press and others that I contracted too many junior players. In 1995 we had a very talented u21 side and I decided to contract many of them. Most of those young players were stalwarts in the years to come at the WP/Stormers. Players like Corne Krige, Bobby Skinstad, Selborne Boome, Percy Montgomery, Louis Koen, Kobus Visagie, etc.

It took some time for the people in charge of rugby worldwide to get to grips with the professional game. I then moved to the UK to coach London Scottish in the Premiership and the clubs were bought by individual businessmen.

London Scottish only lasted a year as a professional club and we as staff and players were not paid during the last part of the season. Luckily, I was offered the Director of Rugby job at Saracens which saved me from packing my bags and moving back to SA.

The owner at Saracens, Nigel Wray, was a successful businessman and ran the club as a business. Many top coaches were plying their trade in the Premiership at the time: Bob Dwyer, John Mitchell, Ian McGeechan, Zinzan Brooke, Dick Best, and Andy Robinson. These coaches all had different styles and for me it was a fantastic opportunity to work in this type of environment.

Clive Woodward was the England head coach and he was very connected with all of these coaches.

Professionalism definitely changed the way we trained because we had more time to cover all the aspects. In the amateur game weight training, for example, was not part of a player’s conditioning but in the professional era the S&C part of training has improved with leaps and bounds. It’s become far more scientific, and the players are far better prepared for the demands of the professional game.

In the amateur game we did not have the luxury of specialist coaches. Most of my career I was the only coach. I started introducing a sports psychologist when I was coaching EP and it was frowned upon. Even in my London Scottish days it was just me. I had to coach everything from skills to scrums, attack, defence to game plans, etc.

At Saracens I had one assistant coach and an S&C coach. Nowadays they have coaches for just about every small aspect of the game. It has become very technical, which is understandable.

Technology has also improved. Game analysis systems, cameras, drones and physical testing is continually changing and improving. All these have made a massive contribution to the professional game.

The game is now played at a faster pace. It has become more combative, and defence has improved to another level through coaching. The introduction of rugby league defence specialists in the beginning of professionalism has changed the way teams defend, and many hours are spent by defence coaches to perfect it.

World Rugby has an obligation to make sure rugby is a safe sport and therefore the laws are amended regularly. I just feel that they will have to get to a point where enough is enough. Maybe the right people should be locked up in a room and not come out of there until they have sorted out the laws of the game. Too many rules are not conducive to keeping rugby a spectacle and the current laws encourage teams to play for penalties, slow the game down, fake injuries, too many stoppages, etc.

We have now been professional since 1996 and because players are now being paid a lot of money, they think that we need more rugby. We need a structured season sooner rather than later. We need a nine-month rugby season from start to finish.

All matches from international to professional leagues should fit into the nine months. Nobody should be allowed to play any matches outside of that window. There must be a month off from rugby, then two months’ pre-season before any competition starts.

Alan Zondagh has enjoyed a 40-year coaching career that has taken him from spells at WP to EP, the Sharks, London Scottish, Toulouse, Scotland, the Bulls and Lyon.